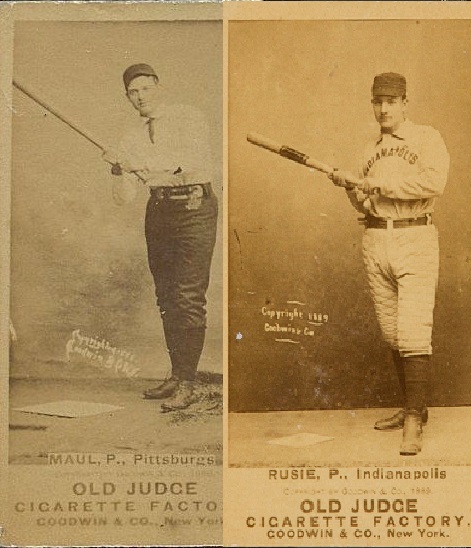

Sometimes a triple is better than a home run. That was probably a line said by a 19th century baseball manager a few times, but you would never hear it today. On June 15, 1889, the Pittsburgh Alleghenys were playing the Indianapolis Hoosiers and Pittsburgh’s Al Maul decided that a triple was better than a home run. Here’s the story of a very rare baseball occurrence.

Al Maul debuted in 1884 as an 18-year-old pitcher. He lost his only start, then didn’t play in the majors for another three seasons. He returned as a two-way player, seeing more time in the outfield and at first base than as a pitcher. He joined the Pittsburgh Alleghenys in 1888 and he was mostly switching between left field and right field in 1889. His pitching was limited to six games and four starts that season, with three of those games coming very early in the year. Coming into play on June 15, 1889, Maul had hit three career home runs. He would add just four more after that day, and once went five seasons between homers.

The pitcher for Indianapolis that day was Amos Rusie, who just celebrated his 18th birthday two weeks earlier. He was one of the biggest pitching prospects of the day, but he also had very little control. He threw extremely hard and it eventually led to big things. He led the NL in strikeouts five times and walks five times, while also winning 20+ games for eight straight seasons. Back in the days of no pitch counts, he piled up walks, strikeouts and complete games.

This game on June 15th in Indianapolis was Rusie’s first career start. His mound opponent was 22-year-old Harry Staley, who would go on to lead the NL in losses in 1889. As you’re reading this recap, realize that Rusie and Staley each threw complete games and the game took two hours and 15 minutes to play. Also, rules of the day made no mention of the home team batting in the bottom or top of the inning. They had the choice and Indianapolis chose to hit first this day.

Two first two innings of this contest were scoreless. Indianapolis broke through in the third with two runs on two doubles and a single. Pittsburgh came right back with three runs in the bottom of the third on a three-run homer by Ned Hanlon, who would start his Hall of Fame managerial career as Pittsburgh’s center fielder/manager a short time after this game.

Indianapolis tied the game with two singles and a sacrifice in the fifth. They soon broke the game open against Staley by putting up five runs in the seventh and another three in the top of the eighth. Pittsburgh wouldn’t say die though, scoring five runs in the bottom of the eighth, before tying the score in the ninth. It was the eighth inning that had the play that made this game noteworthy.

Al Maul came to the plate with Pittsburgh rallying back from down by eight runs to start the frame. They drew two walks and hit two singles before Maul came to the plate and put one over the left field fence at Seventh Street Park. His run would have made it a three-run game, but instead of rounding the bases, he decided to stop at third base and take a triple, one of two he hit that day.

The reasoning behind his odd choice doesn’t apply to the current game. Back then, catchers would play well behind home plate with no runners on base. The easy explanation lies in the equipment from the day. Catchers wore small padded gloves and didn’t have much protection. So to save on some wear and tear, they would make things easier in situations where they didn’t need to be close to the plate. With a runner on base, they were forced to play close and sometimes that would affect their game calling. You had a fireballer like Rusie on the mound, a catcher might be inclined to call more off-speed pitches, making it easier for the batter to know what was coming.

Two days after this game, Pittsburgh catcher Doggie Miller had his finger split open while trying to catch a pitch in the fifth inning and he had to leave the game. Right fielder Fred Carroll went behind the plate and he was replaced in the outfield by Harry Staley. Catching was a tough spot in the 1800’s.

I’m not 100% sure that stopping at third base would ever make much sense on a home run, especially when you’re down by four runs in the eighth inning, but someone thought it made sense. Maul wasn’t the only player to sacrifice a home run to keep the catcher close. It once happened against the Alleghenys once in 1890, when the opposing batter stayed at third base and then had to remain there on a line drive single that was nearly caught in shallow center field. In other words, the other team failed to score a run on a “home run” followed by a single.

Maul would end up scoring on an error to bring the score within three runs. In the ninth, Pittsburgh would score three runs to tie the game, with Maul and Fred Carroll adding back-to-back triples…a legit triple this time for Maul.

The game went to the tenth and Indianapolis hammered Staley to the tune of five runs on five singles, a sacrifice and an error by Doggie Miller. Pittsburgh failed to score in the tenth and took the 16-11 loss. As I said, 27 runs, ten innings and the game took just 2:15 to play.

Al Maul hit 31 triples in his 15-year career, but none of the other 30 were quite like the one he hit on June 15, 1889.

Here’s the boxscore from the day. Astute observers will notice a third Hall of Famer in the score along with Hanlon and Rusie.

Here are links to the previous Game Rewind articles:

Pirates vs Cardinals, September 28, 1937

Pirates vs Yankees, July 5, 1923

Pirates vs Reds, April 27, 1912

Pirates vs Indians, July 17, 1999

Pirates vs Cubs, April 21, 1991

Pirates at Reds, April 14, 1909

Pirates vs Reds, April 14, 1960

Pirates at Braves, August 23, 1971