Back on April 16, 1915, Pittsburgh Pirates manager Fred Clarke gave a young pitcher his first Major League start. Clarke, who was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1945, would be joined in Cooperstown by Charles “Dazzy” Vance ten years later. However, on that rainy day in 1915, Clarke had no idea that his 24-year-old starting pitcher would end up as the Major League strikeout king for a long stretch in the 1920s.

Before the April 16th game against the Cincinnati Reds, Fred Clarke told the local newspapers that he would either start Babe Adams or Joe Conzelman in the third game of the season. After the game, Clarke’s choice was questioned and he said that he wanted to give the new recruits a chance to pitch before deciding which one to get rid of by May 1st. Teams were able to have an expanded roster in early season games, but they had to be down to 21 players by May 1st.

The writers had a good reason to question Clarke’s decision. Adams had a 2.51 ERA in 1914, and his 1.03 WHIP (which obviously wasn’t a stat back then) was best in the NL. Vance also didn’t give any reason to make it seem like a good decision. In 2.2 innings, he allowed three runs on three hits, with five walks and one hit batter. He would eventually become the top strikeout pitcher in baseball, but on this day he failed to pick up his first big league punch out.

Teams had Spring Training back then, so the Pirates got a good chance to see Vance before making their final decision, even if they didn’t give him the big league opportunities. He first pitched on May 16th in a Pirates vs Pirates game. He allowed four hits over three shutout innings in that game.

He made a bad impression just two days later when he gave up seven runs on 14 hits in five innings against the younger players in camp for the Pirates.

On March 24th, Vance allowed one run over four innings, but it could have been worse. Quoting the Pittsburgh Press game recap, “he was as wild as a March hare and sent two men to first” to start his first inning. That was followed by a sinking liner to center field caught by Jesse Altenburg, who threw to second for the second out, then the ball was thrown on to first base for a triple play. It’s interesting to note here that Vance was pitching for the younger players. A move like that during Spring Training at this time usually signaled a demotion on the depth chart.

Pitch counts were not a thing in 1915, as evident by the fact that Vance pitched five innings on two days rest during the second week of Spring Training. He jumped back to the “A” squad (called the “Regulars” back then) and allowed three runs on five hits, with one walk and two strikeouts.

Vance pitched three days later in a wild game, this time facing the Regulars. He went four innings and allowed just one run, despite five hits and five walks.

On April 3rd, Vance was finally able to face a different team and made quite an impression. Going up against a minor league team from Nashville, he pitched a complete game, allowing two runs on seven hits and four walks.

Vance pitched the final exhibition game of the season on April 13th against Indianapolis and he threw another complete game. Notice that he went nine innings just three days before his lone big league game for the Pirates. He lost 2-1, allowing four hits, with one walk and six strikeouts.

The news about Dazzy Vance leaving the Pirates came six days after his lone regular season appearance, but it might be best that they didn’t wait until May 1st to make that decision. That would have qualified them for having the worse day in baseball history.

On May 1st, the St Louis Browns announced that they had come to an agreement to sign George Sisler. The Pirates had originally signed Sisler at 17 years old, but his contract wasn’t deemed to be official because he needed his father’s signature to sign a deal as a minor. There was a case held by MLB to determine if Sisler would become a free agent. According to the local papers on May 1st, the Pirates came to an agreement with the Browns to allow them to sign Sisler, who was on the suspended list for Pittsburgh. If you don’t know, Sisler was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1939.

What makes matters even worse is the news headline in the Pittsburgh Press right above the Sisler signing which notes that the Pirates passed on signing Grover Alexander because they considered him a “bad actor”. Alexander was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1939 with Sisler.

As it was, the Pirates gave Vance just one chance before deciding to send him on an optional assignment to St Joseph of the Western League, where he pitched in 1914. Vance went 17-15, 2.93 in 264 innings with St Joseph, then made his second big league start with the New York Yankees in August.

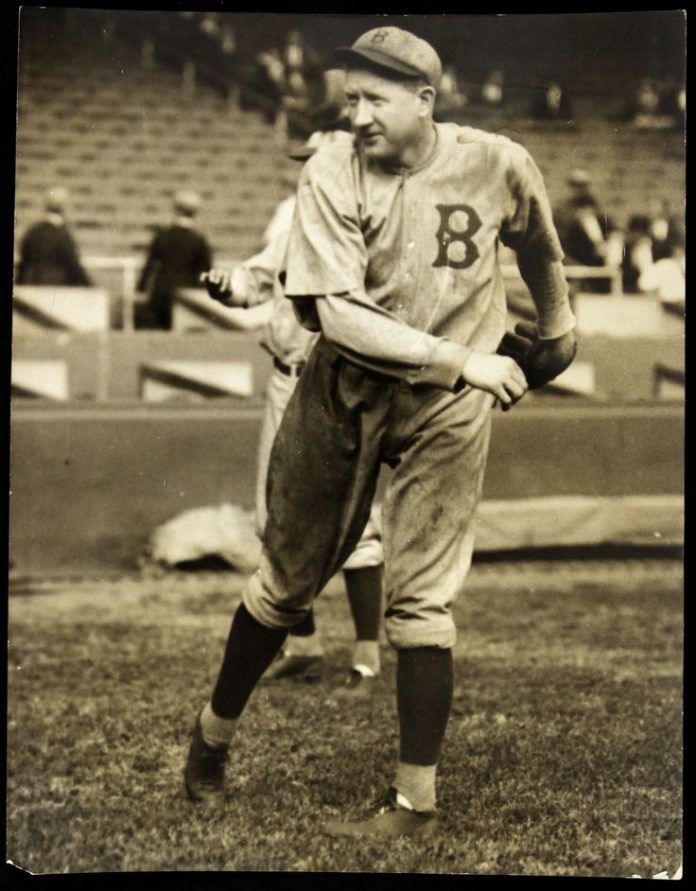

He was pictured in the newspaper for the Forbes Field Opening Day celebration on April 22nd, which appears to be the only surviving picture of him with the Pirates.

The Pirates didn’t regret holding on to Vance for quite some time, and it really didn’t look like a bad decision at the time, though they were pretty bad in the standings at this point and things got worse in a hurry. Vance couldn’t have done anything to hurt their 65-89 record in 1916, or the low point in 1917 when they went 51-103.

There’s no guarantee that holding on to him would have resulted in him becoming a star down the line. That being said, imagine adding a Hall of Famer to the 1925 World Series champs or the 1927 team that could have used him in the World Series. Maybe they make the 1924 and 1926 World Series with him, two teams that missed first place by a combined 7.5 games.

Vance would join the Brooklyn Dodgers (Robins) in 1922 and reel off seven straight NL strikeout crowns, while piling up 133 wins during that stretch. He went 26-14, 2.97 in 361 innings against the Pirates in his career.