It’s Saturday in Pittsburgh, a hot but tolerable 76-degree evening with a late sunset. Tonight, a full PNC Park will watch Dan Fox beat Rickie Weeks at baseball.

Dan Fox is 45 years old, tall but hardly wiry, bald and framed by Oakley glasses. His former internet baseball column was named after physicist Erwin Schrödinger and his Xbox gamertag is inspired by a work of John Milton.

Rickie Weeks is 30, shorter than average height but featuring bulging biceps that swing a heavy bat. He is a former All-Star for the Milwaukee Brewers and college baseball player of the year, and his dreadlocks add some weight to his 215-pound frame.

Though Weeks enters the game with a .400 average in the month of June, Fox has orchestrated the plan that will cool Weeks’ hot streak. After Weeks draws a six-pitch walk, he hits two ground balls to Pittsburgh shortstop Jordy Mercer and a pop fly to left fielder Starling Marte to end his 8-game hitting streak.

The Brewers lose to Fox’s Pirates 2-1, making them the first Pittsburgh team to get to 50 wins before the month of July. He put the ball in play, but Weeks had simply been out-Foxed.

Why Shift a Defense?

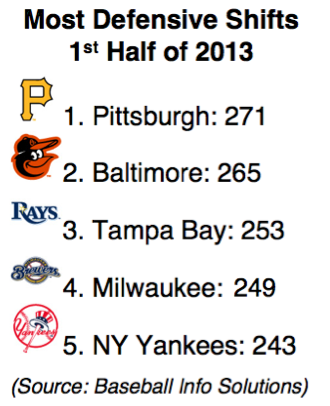

Fox, the Pirates’ director of baseball systems development, and quantitative analyst Mike Fitzgerald are the minds behind a defensive scheme that has pulled MLB’s most alignment shifts in baseball on balls in play (according to Baseball Info Solutions) and turned the most batted balls into outs. The Pirates have adopted Fox’s plan gradually over the last three years, and now the results are evident for the defense that is MLB’s second-best team at preventing runs this year.

Fox, the Pirates’ director of baseball systems development, and quantitative analyst Mike Fitzgerald are the minds behind a defensive scheme that has pulled MLB’s most alignment shifts in baseball on balls in play (according to Baseball Info Solutions) and turned the most batted balls into outs. The Pirates have adopted Fox’s plan gradually over the last three years, and now the results are evident for the defense that is MLB’s second-best team at preventing runs this year.

“Our willingness to be more aggressive in optimizing our positioning has definitely been one of many factors,” Fox says. “I definitely think it’s helped.”

Let’s take this back to basics: A baseball team gets to put 9 players out on defense. The spots for the pitcher and catcher are largely fixed, but the seven other players have been placed in the spots teams believe can best cover the two acres of grass and dirt and three bases on the field. Over the years, those players have converted about 70 percent of their plays into outs.

How do you improve that? You look at where the batters hit the baseballs your defense is trying to grab and throw. Today, we have data that tells us where and how hard the batters are hitting the ball, where the pitchers give up their ground balls fly balls and the best way to defend those balls to throw out the batter before he can reach base.

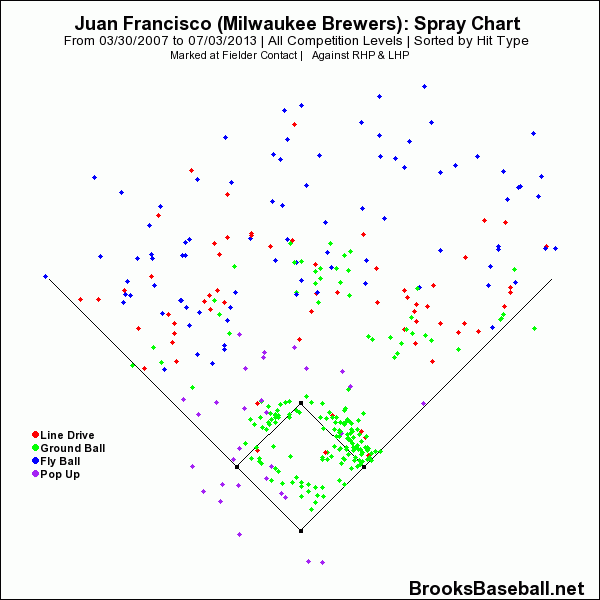

See how the Pirates aligned the defense for right-hander Rickie Weeks, then hover over the image to see how it changed for left-hander Juan Francisco.

Look at Juan Francisco’s spray chart, especially the ground balls in green, to see why the Pirates put three infielders on the right side.

Given all that, Fox says, it is only logical to align a team’s defense batter by batter based on where that player hits the ball most often. Dramatic shifts include putting three infielders between first and second base for left-handed pull hitters like David Ortiz and Adrian Gonzalez. Less noticeable shifts include fading Neil Walker further up the middle or having Pedro Alvarez stay close to third base to prevent a double down the line. The style of the pitcher on the mound can also change where defenders line up, and coaches will even change the alignment for a batter from at-bat to at-bat.

Fox doesn’t even like to call them “shifts,” as it implies a change from what is normal. Fox wants the fielders to consider the formation normal and logical even if it’s not typical.

“You want them to be thinking ‘This is our normal positioning. This is where I’m supposed to be. I’m not out of position. I am perfectly in position because that’s where the ball is going,'” Fox says.

Instilling and Installing New Ideas

How did Fox implement the system that helped catapult the Pirates from the National League’s worst fielding team (67% of balls into outs, 76 runs below average) to one of the league’s best fielding teams (72% of balls into outs, 31 runs above average)? Very gradually. Fox’s team provides the information to Pirates manager Clint Hurdle, third base coach Nick Leyva and minor league managers. The coaches then communicate to the players, often with visuals like spray charts of batted balls, about the benefits of shifting positions based on the hitter.

“We’ve definitely been more aggressive. The numbers don’t lie,” Leyva says. “And to this point we’ve been pretty successful, so they’re buying into it more on a daily basis.”

The results have been strong in defensive efficiency, turning batted balls into outs, from the minors to the majors.

- Pittsburgh Pirates: 1st of 30 teams

- Indianapolis Indians: 1st of 14 teams

- Altoona Curve: 2nd of 12 teams

- Bradenton Marauders: 5th of 12 teams

- West Virginia Power: 5th of 14 teams

“We just go play a position, line up where we do,” says Josh Harrison, in the Pirates organization since 2010. “It doesn’t really affect us as much as the pitchers.”

“That’s the opposite of what I said,” responds pitcher Bryan Morris with a laugh.

“Really?” replies Harrison. “For us, yeah it felt weird because we are so used to playing a certain area, but it works both ways. There may be a few hits given up, and we’re like, ‘Dang, if I would have played here I could have gotten it.’ But regardless of where we line up, we still have to throw the ball.”

How Much Shifts Help

Harrison introduces a good point: players and fans can be frustrated by the balls that go past where a fielder normally lines up because he has been shifted to another spot. Those glaring hits are offset, and more, by the extra outs fielders get with the optimized positioning. Since 2007, MLB teams have shifted more and converted 1 extra ball out of 100 into an out.

Since Fox and Co. started to implement the new defensive system in earnest in 2011, and expanded it since, the defense has gotten better and better at preventing hits and runs. Over the last four seasons, the Pirates have improved dramatically from their spot at the bottom of most fielding metrics.

- 2010: -77 runs saved, -57.7 UZR, 67.1% batted balls into outs, 449 plays made out of the zone

- 2011: -29 runs saved, -18.2 UZR, 68.4% batted balls into outs, 496 plays made out of the zone

- 2012: -25 runs saved, 0.4 UZR, 69.7% batted balls into outs, 492 plays made out of the zone

- 2013: 31 runs saved, 13.4 UZR, 71.7% balls in play into outs, 576 plays made out of the zone (projected)

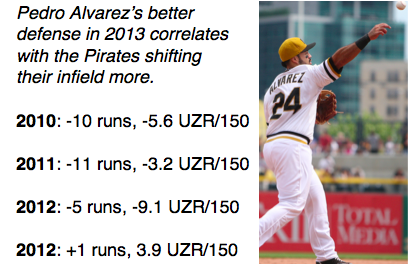

Proper credit must be given to the fielders themselves, especially the improvements made by second baseman Neil Walker and third baseman Pedro Alvarez, plus the addition of elite defensive left fielder Starling Marte. The correlation between more aggressive shifting and better defensive play is strong, though. Coach Leyva sees it every day.

“Instead of having to dive for a ball, if they’re sitting in front of it. It makes a whole lot of difference,” Leyva says. “[Our fielders have] good range, but when we do it by position and put them in the right spot, it increases their range.”

The Pirates pulled more shifts in the first half of 2013 than in the last two full seasons combined. According to Baseball Info Solutions, the team has saved five extra runs using defensive shifts (as many runs as Neil Walker’s hitting has been worth above an average MLB second baseman), but BIS analyst Ben Jedlovec says the true gain is even higher.

“I think it goes well beyond the five runs that we’re citing there,” Jedlovec says. “The Pirates are getting better at making subtle positioning changes… You can take a guy like [Pedro Alvarez], put him in the right spots, and that can make up for a lot of shortcomings agility-wise.”

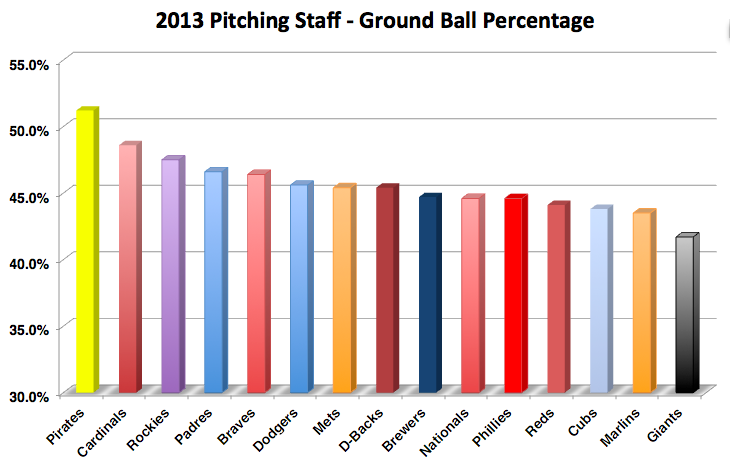

Pirates’ pitchers have benefited most from the infield shifts, especially ground-ball-generating starters Jeff Locke, A.J. Burnett and Jeanmar Gomez. Giving up a lot of grounders means not giving up home runs (the Pittsburgh staff has the 3rd-lowest homer rate in the NL) or other extra-base hits, but it only works if the infield can field the ground balls. With the shifts and range of Walker, Jordy Mercer and Clint Barmes, the Pirates’ infield has been one of the five most efficient in baseball in addition to the outfield being top five.

Pirates general manager Neal Huntington says run prevention starts on the mound, and Bucs’ pitchers have allowed the fewest hard-hit balls in the Majors, according to ESPN’s Mark Simon. The next step, though, is the quality of the fielder and where he is positioned, with Huntington adding that his team has been more aggressive this year with changing typical positioning.

“We do feel there’s certainly been dividends,” Huntington says. “There’s been that four-hopper rolled that’s rolled through an open hole where a [fielder] is conventionally positioned, but there’s been a number of time where there’s been a ball smashed up the middle and there’s Neil Walker.”

You have to watch closely to see the benefits of the Pirates’ plan; it does not leap off the screen. Pittsburgh has had the fewest Web Gems appearing on ESPN’s Baseball Tonight this year. Fielding percentage often only considers errors on plays where a fielder is in a spot and doesn’t grab the ball. Good positioning allows a fielder to start closer to where the ball ends up, likely reducing the chances for flashy diving or running plays.

The Pirates’ fielders have made the second-most plays in baseball (294) “out of zone,” meaning outside the areas on the field in which an average player is able to catch a ball half the time. The first-place team is the Milwaukee Brewers, a team run by shift-endorsing manager Ron Roenicke.

“It helps a lot. More and more teams are starting to do it,” Roenicke says. “And it makes sense. If you can get them in the right spot and the pitching staff throws it in the right location for you, it’s a big advantage.”

The advantage was in the Pirates’ favor through 81 games. Fox doesn’t predict the Bucs will lead the Majors in defensive efficiency the rest of the season (“Any time you are first in anything, there is going to be some regression”), but Jedlovec from Baseball Info Solutions says good defensive stats in the first half are still solid predictors of good defense in the second half.

Get Inside Their Heads

One other effect the defensive shift can have is the old-fashioned mind game. Not only can regular shifting on a pull hitter reduce his batting average by about 30 points, seeing hard-hit balls fall into the glove of a third baseman who is in right field can get under a hitter’s skin. It certainly did for Yankees’ slugger Mark Teixeira when he hit left-handed.

“It can change their approach,” Jedlovec says. “Teixeira came out and said ‘I’m going to start raining down bunt… I’m gonna fool ’em. I’m gonna make them stop shifting against me.’ You can tell it threw him off the first half of the season.”

It’s all about comfort level. Pirates’ fielders were uncomfortable at first moving from their normal spots on the field, sometimes to the opposite side of a base. But as they adapted and saw more balls fall into their gloves, they bought in.

“It was a little different, playing in different spots,” says shortstop Jordy Mercer, drafted by the Pirates in 2008. “Now I believe it. We do scouting report, see where guys hit the ball and where pitchers throw.”

Now the Pirates are comfortable moving from spot to spot on the field. It’s the hitters who have not adjusted. In fact, today’s Major League Baseball may be heavier on pull hitters now than ever before.

“People pull the ball now. The ability to hit the ball the other way has really trended down,” Pirates manager Clint Hurdle says. “It’s more of a dinosaur than anything.”

Now even right-handed hitters like Rickie Weeks see fielders shift on him. He understands though, as his Brewers are just as aggressive with moving around defensively as the Pirates are.

“I think there’s a lot more people paying attention to scouting reports and where guys hit the ball,” Weeks says. “Sometimes you get beat by it, sometimes you don’t.”

A Changed Team

On that hot Saturday night, Weeks was beat by it. For all the frustrating ground balls that hitters Ryan Howard will dribble through an open side of the field, there are several less noticeable strengths of the shift. Walker fields a ball on the opposite side of second and throws out a runner hustling to first. Mercer is in the perfect spot for a one-hop ground ball. Or in the outfield, McCutchen is on the warning track within a couple seconds to take away a possible double.

What is different about this year’s Pirates? What will prevent a third-straight collapse from breaking the heart of a city that wants to trust its baseball team? Can the team keep winning for the fans that are beginning to fill PNC Park and give it new life? Will Fox’s strategy keep paying off?

“We’ll see how it goes,” Fox says.

Fox may not have a crystal ball, but he has a plan. And his plan has helped the Pirates become baseball’s run prevention machine.