All human being development boils down to first finding our own brachistochrone curves of ascent.

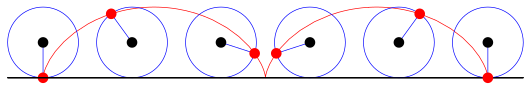

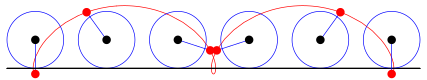

A brachistochrone curve is an optimal cycloid that allows the fastest travel between Points A and B, with the least amount of friction. If you apply this to baseball development, it’s the most efficient path a player takes to go from wherever they currently are (Point A) to their perceived upside (Point B). I discussed brachistochrone curves as they related to baseball development in more detail earlier this month, when breaking down the development issues for the Pittsburgh Pirates. An example of the brachistochrone curve can be seen in the image below, represented by the red line. For the purposes of baseball development, this would need to be inverted to show ascent, rather than descent.

In order to find a brachistochrone curve, you need to find a player’s Trochoid. That’s the curve measured from a point fixed to a circle. It reveals the cycloid of the player.

Lost yet?

This is all abstract, with an attempt to remove the thought process of player development from the physical realm, and shift into a realm where the entire essence of a player can be summed up as a circle rolling down a line.

Inside this circle, we find the center of the player, represented by the black dot above. Separate from that dot is a red dot, which for the purposes of player development, is how far the player extends themselves from their center — which is the comfort zone. This red dot measures a player’s trochoid as the player continues down a straight line — with the line representing the passage of time. The red line mapped out is the player’s trochoid, which helps to identify the brachistochrone curve.

We all have trochoids that measure our daily, weekly, monthly, and even yearly production. They can be measured as “Common” (also called a Cycloid), “Curtate”, and “Prolate”. The purpose of this article is to find a deeper understanding of human trochoids, and how they relate to Major League Baseball players. I don’t want to use specific players in this article, so I’m going to subject myself to the study, to provide a real-life example of how these trends impact us.

If you thought Facebook was Meta, you’re about to learn something about the way I’ve been running Pirates Prospects for the last two years.

COMMON (CYCLOIDS)

Let’s start with the best. The common trochoid is called a Cycloid. This measures the curve of a circle if you place the red dot on the outer edge of the circle.

If a player is the entire circle, the black dot is his center. If a player is not centered, he will simply not be able to roll down a straight line of time, much less map out his potential. We’re going to assume every player in pro ball is centered, capable of progressing down the straight line of time without sending the circle bouncing around like a car whose wheels aren’t aligned.

If a player is properly centered, the next point is identifying his performance point. That can be mapped out on the Cycloid below as the red dot.

In baseball, we focus on potential and future values for every player. Imagine that all of a player’s potential fits perfectly inside of his circle. More talented players will have a bigger circle, where their center is higher above the floor than less talented players.

The goal is to get a player to maximize his expression, which would be represented by placing the red dot on the edge of the circle. From here, you see the common trochoid, or cycloid, which is the essence of a player.

If that circle above represents a baseball player, it’s showing his progression every day, week, month, or year. A better way to look at it is below:

Imagine the above represents six games in a week, and each red dot represents the performance of a player in each game. The black line represents the passage of time as you extend horizontally down the line. In a vertical sense, you’re tracking how far a player is playing above the base level. For baseball purposes, imagine that line is the MLB replacement level. Any performance below the line belongs in Triple-A, while any performance above is measured in MLB success.

The player above spent two games a week at replacement level, two games at around average performance, and two games above-average. We don’t know their relative circle size, so we don’t know if their average is better than another person’s peak, and we don’t know how high up their peak goes. All we know is they will have a natural flow that will usually lead to a split where they have good games, bad games, and neutral games each week.

You could say “why doesn’t a player play every game above average?” This would be ideal, but it ignores that each player has a legitimate trochoid to map out. Every player is human. Every player will have ups and downs with their performance in a game that is played almost daily for six months. Baseball is a hellacious marathon. Even the best players go 0-for-4 each week. The key is maximizing your potential flow, so that you can take advantage of the highs to offset the lows each week/month/year.

PERSONAL EXAMPLE

I said I would give an example of myself to explain these, but I don’t think I’ve ever operated under a Cycloid pattern in my life. To me, this is the “wake up at 6 AM to go to work for eight hours, come home, watch TV, and go to sleep at 10 PM every night” trochoid. My ADHD could never.

This is what we’re all taught from the age of five, when we have busses that pick us up as children and shuttle us to a second building to spend among people who aren’t our families for 13 mandated years. By the time a baseball player from the United States is good enough to be in an MLB organization, this is their indoctrinated training, and this is the unspoken goal of production.

Very few actually accomplish this.

You could say this is the ideal daily trochoid for anyone’s performance. Wake up, reach the peak of your performance at a set time, and then go to bed and do it all over again the next day. If you think of it that way, it almost looks like a clock, tracking performance points across time.

Not everyone has that perfect cycloid pattern, where they maximize their abilities every single day, week, month, year, and reach a restful eight hours of sleep like clockwork.

Most people are either a Curtate pattern, or a Prolate pattern.

CURTATE TROCHOIDS

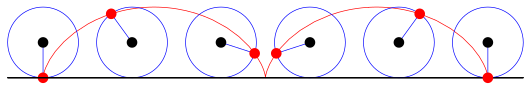

Curtate patterns measure out the path traced by a performance point that is less than the value of the radius of the rolling circle. In baseball terms, a player isn’t performing up to his potential. When compared to the Cycloid pattern above, you can see that there is less upside, but also less downside, in the mapped out line of progress.

The image above is a very common problem in baseball development, and in life. A Curtate never really hits the ground in performance or drops below the production line, but never really reaches the highest potential at any point in time. And that’s especially frustrating when everyone can see the circle of potential.

Imagine the black dot in the center is our sense of self. The line at the bottom can be anything. It can be A-ball. Triple-A. The Major League level. Teaching. Professing. Presidenting. Anything. Everything. We eventually reach a point where we can roll along the line with an established center that keeps us above the line, which is represented by the black dot.

From there, we always try to expand from the center with our production. That can be difficult, because we don’t always have the confidence on knowing how to expand, or how much to expand. This all boils down to the act of expression.

Sometimes we can be too within ourselves; too reserved. If you think about the black dot as the core of who we are, and the red dot as your level of expression, then the goal of maximizing expression is to get the red dot to the outer edge of the “circle”. The curtate path below shows the upside limitations when a player can’t fully express themselves.

In order to achieve the common cycloid from a curtate pattern, a person needs to maximize their expressive ability. They need to be less reserved, more expressive.

In their development system, the Pittsburgh Pirates now have hitters developing in an almost free-swinging way for a period of their development. This is what they’re doing when they tell hitters to not hold back during that exploratory development period: They’re trying to push the red dot out as far as possible from a reserved curtate flow, expanding the production flow of players to a more common cycloid.

In the Major Leagues, I don’t think a curtate pattern is a problem, so long as the player’s center is above the replacement level line. This does lead to fan frustrations. The road to post-prospect hell is filled with players who were good enough to play in the majors, but not good enough to stick long-term, due to the fact they couldn’t fully express their potential. I don’t want to go into theories of who I feel had curtate performance in their careers, but if you’ve followed this site over the last 15 Pirates seasons, you probably have watched players who weren’t fully expressing their potential from their reserved center of self. They’re the players who seem “safe” — rarely doing anything big, but also rarely falling below the minimum line of production.

PERSONAL EXAMPLE

On this site, I had a curtate cycloid flow in 2022. My only goal that year was to publish a full year of article drops, with seven articles every Tuesday. The site was eventually expanded to produce daily articles, but the workload was less than it had been in the past. I was less focused on expressing the site to its maximum potential, and more focused on maintaining a steady, productive flow all season.

My biggest theory in the game of baseball, and in the game of life, is that most people lack a sense of self. They can’t even picture their circle of potential. They might know how to get centered, but they don’t know where that center of self resides above the line of the level where they want to perform. Without this knowledge, it’s nearly impossible for them to adjust the red dot of expression accurately. We all seek so much validation in establishing our circle and center that we don’t have time to express our potential to the fullest from the ideal circle location.

As a result, my belief is that some people don’t ever really grasp how good they are, or how good they could be, as their endless quest for validation keeps them with an eye to who they could improve to in the future. They’re growing the circle. They never really stop the endless quest for improvements and shift into a mode where they feel the circle is big enough. They don’t shift to a point where they try to expand the red dot to their maximum abilities at the current level.

In the game of baseball, it’s the job of a player development system to first allow a player to identify his sense of self. We do that in the prospect industry before a player has even touched foot on a professional playing field. The Pirates draft a player, and five minutes later, everyone on the internet is projecting that player’s circle, center, and the path his red dot could map out in the future. It’s all very unfair to the player, who is ultimately in control of where the red dot sits, and who might not even personally validate the public’s opinion of his circle size or centered black dot.

Inside the game of baseball, the Pirates and other teams have an ultimate power to guide the player on who they are. This is the main reason I am a huge fan of the individualized development system implemented by John Baker. The concept might sound like a buzz phrase, and I don’t know if Baker or the Pirates see this as I do, but there’s a value in a larger organization giving an individual the space to be themselves. It’s a form of validation, which may not have been implemented upon the player by their family, friends, or previous stops in their baseball career. We all assume that every pro player has the ability to validate themselves and see themselves in the same light as their loftiest projectors, but in my 15 years around this game, I can tell you that it’s the exception when a young player knows himself so securely.

A curtate cycloid flow always keeps you above the line, even if you don’t always maximize your abilities. It’s a conservative approach. If your centered self is elevated enough, your curtate heights can still exceed some people’s common cycloid heights. If a player is above the line, but the production is lacking, then the red dot of expression might need to be expanded out from the center.

The problem with this type of extension is that it can often go too far…

PROLATE TROCHOIDS

Are you ready to spiral out with prolate trochoids?

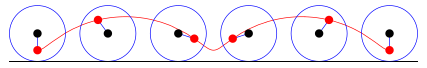

This is the other frustrating MLB player to watch. This is the player who almost goes beyond his capabilities. In doing so, he over-extends himself and ends up eventually dipping below the line. In order to ascend again, the player needs to briefly reset and almost backtrack.

This player as a hitter can be frustrating, because they become streaky. Yes, you get the production that is over their head, but you also get just as much production that is below their level.

Imagine each of those red dots above is a performance on a given day of the week. How much do you celebrate the two highs, seeing how they’re offset by the two below-the-line lows, and the two below-average midpoints? If a player’s black dot of self is barely above the MLB replacement level line, then you might get four Triple-A performances in a week, with two games that are beyond a player’s potential. We always wonder how a player can keep those two games and improve the other four.

This is the age-old “He’s trying to do too much” and it’s the best way of displaying it. This is the person who overextends themselves to the point where it’s eventually a detriment. These players need to be managed if they remain on a prolate flow. If you’ve got a curtate player, you can throw them out there every day with no concerns about a detrimental dip in production. You won’t get the excessive highs, but there’s value in stability.

A player with a prolate pattern needs to be benched before he dips below the line. Or, long-term, he needs to scale his expression back in every single game, which sounds scary to scale back the two productive points, but results in improving the other four. Ultimately, he needs to find out how far out he can push the red dot before he eventually enters prolate mode, which looks like — if you extend the pattern out long enough — a spiral.

It’s never good when human beings are in a spiral pattern.

PERSONAL EXAMPLE

This spiral pattern has been on display on this site in 2023. After finishing 2022 with curtate production, I decided to push my red dot beyond my circle of potential. I took on too much.

This was intentional, to get a better understanding of how I reached severe burnout and massive health problems in 2018. To this day, I still am hesitant to return to anything close to my old work patterns, simply because of how detrimental it was for my physical health. In 2023, I decided that every time I reached burnout, I would take a break.

There were several times where I took breaks from publishing this year. We only care about career performance and potential in this society, but there were some periods where I was burning out because I was putting a lot of my energy into my real life: My mental health, where I would live in 2024, or helping family in my life. Baseball players have this as well. Some players are over-extending themselves in life, away from the baseball field, which makes it impossible to maintain a productive flow at work which maximizes potential. The best you can do is try to quickly get back to a point where you can also maintain a productive flow at work.

Regardless of the reason a player is over-extending themselves, a prolate pattern isn’t ideal. It eventually leads to a drop below the line, and almost a backtrack before the player can progress forward again.

By that way of looking at it, every single pitcher who has had Tommy John surgery was on a prolate pattern, prior to us finding out that pattern from the injury.

CYCLOID VS CURTATE VS PROLATE

Every player is either a common cycloid, a curtate pattern, or a prolate pattern.

They’re either maximizing their abilities as a common cycloid (and it’s unfair to call that common, as I think there are more curtate and prolates combined), or they’re stuck between being too reserved (curtate) or too loquacious (prolate) in their forms of expressing themselves.

I think the key to baseball development is realizing that the perfect cycloid is nearly impossible to achieve. The best approach is identifying the curtate and prolate players, and then trying to either throttle them back, or push them to do more. The risk is that you could turn a curtate into a prolate, which is a completely different struggle that a player wouldn’t be used to handling.

There’s also the possibility that a player hasn’t elevated their black dot above a higher mental line. Some players might be performing relative to their belief that they are a minor leaguer until an organization elevates them higher. Other players have a center of self that is Major League ready, with their biggest struggle coming from expressing themselves from this center point. The ultimate challenge is that it can take a player several years to get the proper flow once he’s elevated himself above the Major League line.

BASEBALL PLAYER DEVELOPMENT

The Pirates, and every organization in the game, need to provide a system that allows the player to mentally elevate his centered sense of self above the Major League line.

They need to maximize the circle of potential, which can be done through teaching new pitches, positions, or adjusting mechanics. In some cases, a player needs to elevate his sense of self above the MLB line. In other cases, he needs to widen his circle, to improve the potential upside.

Aside from maximizing potential, and centering a player with a Major League mindset, the team needs to help a player find the proper level of expression, to establish a productive trochoid pattern.

All of this is intangible, though I do believe there are modern-day stats that indicate whether a player is on a curtate or prolate pattern; along with indicators of whether their mindset needs to be elevated, and indicators that they may need more coaching.

The ultimate challenge for any team is figuring out what a human being needs. Is it validation of self? Is it more knowledge and training? Or, is it just the experience of expressing themselves, until they reach the point where they’ve got a productive, season-long curtate flow?

One wrong move could derail a player’s career for years, or perhaps life. The right move could unlock a flow potential that very few humans can achieve.